Notice: Views expressed in this article are my own. All opinions are own. The opinions expressed here belong solely to me and do not reflect the views of my employer, co-workers, former corporation (ServerPress, LLC), corporate officers or employees.

The debacle between WordPress.org and WPEngine has shaken the FOSS (Free Open Source Software) world, with the potential to impact over 40% of the Internet’s websites. This ongoing crisis not only strains relationships between the companies but has also divided employees, clients, and community members. It is like burning oil—creating noxious fumes and stifling lawsuits that may permanently change the landscape of the software we all trust and use. To understand why this is happening, we’ll need to dive into some uniquely intimate insights about the players at hand, as well as reflect on how this affects FOSS and what could be done to salvage the fragile ecosystem.

Why Open Source Matters

End users and nescient enterprises may not care about FOSS, but they should. Unlike its completely commercial counterpart, FOSS tends to outpace its commercial equivalents in innovation and maturity, partially because of its transparent and viral nature. Critical issues are often disclosed and discussed openly, with far greater scrutiny than in their commercial counterparts. In my early days as a Microsoft Solution Provider, we sometimes found critical bugs in products and would report them to Microsoft’s provided and paid-for MSDN channels, never to hear from them again. In the profit-driven world, such transparency can be a threat to margins. In contrast, WordPress.org’s trac system allows virtually anyone to obtain a unique ticket number regarding any reported issue and collaborate with others about it. The trac system itself is open-source software. The hyper-evolution abilities of FOSS don’t stop with transparency; its more viral component is embedded in the copyleft licensing terms that entitle all parties the ability to copy, modify, and redistribute the software. Charging money for such modifications, distribution, and services is perfectly legal if not encouraged. Then there is the process of actually running the software and providing it as a service, also known as SaaS (Software as a Service). While usually not covered under open-source terms, the execution of the software and providing access to its behavior and results is a large, profitable business. Capitalism and open-source are more intimate bedfellows than they are distant neighbors.

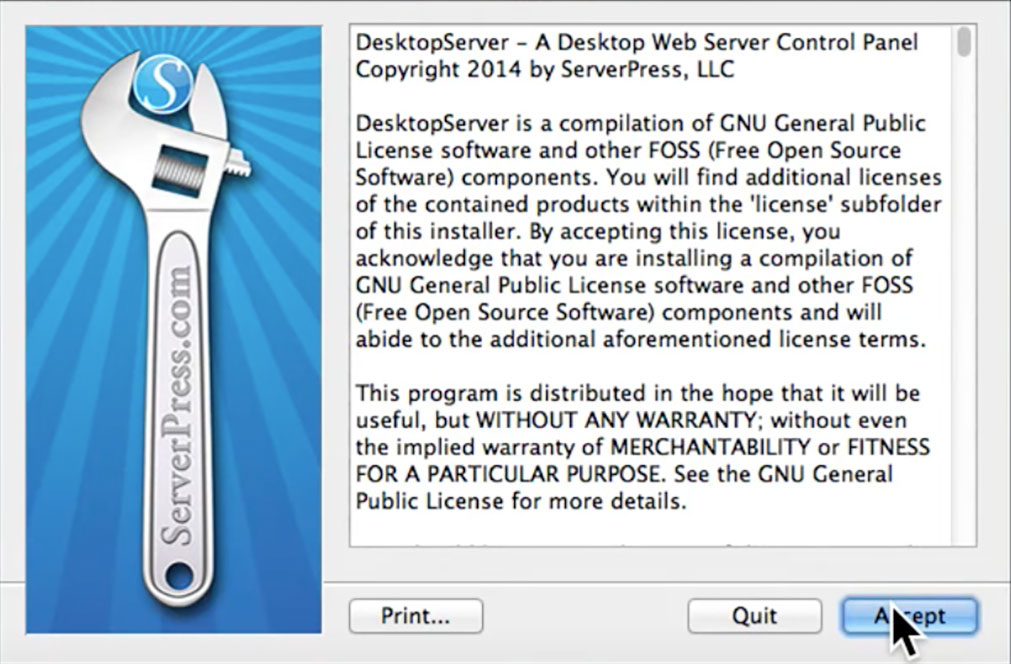

However, what is frowned upon is inhibiting others from having the same rights and freedoms with the software. Unfortunately, some end users and amateur developers are less likely to take notice or care. As the founder of (now closed) ServerPress and creator of DesktopServer (a localhost development server that competed with WPEngine’s LocalWP), I received less than a handful of source code requests; included were government contractors wanting to vet the code for secure facility use and a third party that wanted to modify it for Intranet/LAN-only use. We honored requests that were made possible by FOSS licenses. After all, DesktopServer was created with FOSS. For others in the WordPress community and hosting provider businesses, the importance of open-source is undeniable. It is as essential as the oxygen in our atmosphere, and as we are learning, just as flammable.

No Small Burden

In my last article, I talked about the rising costs for individual FOSS developers, with trusted code signing certificates going from $50 to over $1,000 a year, and the rather odd and literal “Mafia” characters that control that. But that has never been a problem for WordPress developers, as they could submit their creations through a trusted, central directory that reached everyone. The majority of the code base that drives the world’s websites came from one trusted source: WordPress.org. This is no small feat and is a burden that extended beyond the update service and into a backlog of labor for code vetting against vulnerabilities, malware, and privacy concerns. In addition, there’s bandwidth for support forums, bug tracking, statistics gathering, and resources for a11y accessibility, translation polyglots, and documentation. On top of all that, there are costly WordCamps, which were non-profit but had to change or cease altogether. As it stood, there was one individual who was responsible for coordinating and footing the bill for all of that: Matt Mullenweg. The value of this burden is widely debated. But a burden it remains, and everyone who used it paid virtually nothing for it, WPEngine included.

Burning Bridges

A sure way to burn bridges is to bite the hand that feeds you. Automattic invested in WPEngine as part of Automattic’s initiative to purposely invest in companies that supported the WordPress.org ecosystem and hopefully lessen the aforementioned burdens. But I doubt they anticipated the kind of long-term results they would inspire. WPEngine made the decision to compete with Automattic’s “WordPress VIP: Enterprise” with a simpler name, “Enterprise WordPress.” WPEngine targeted the same market and began to eat into Automattic’s profits, while continuing to enjoy the benefits of not having to maintain the WordPress.org ecosystem. Perhaps Automattic figured there was plenty of room for competition and hoped WPEngine would at least pay for resources to upkeep their own customers. But according to Matt, and everything we know thus far, that never materialized. WPEngine continued to sell services that were fully dependent on their competitor’s donations and availability of free services until Matt shut down update services to them on September 26, 2024. This forced WPEngine to come up with their own mirror update servers, but it still does little to nothing for the developer community at large.

There will always be players who want to use FOSS legitimately to earn money. At ServerPress, our mission was to help WordPress developers create and deploy websites to capable hosting providers. Both manually and automated, we deployed hundreds of thousands of websites. It was in our best interest to work closely with hosting providers in open-source for compatibility. Our company mantra was to be hosting provider agnostic. We did not favor, suggest, or receive any affiliate dollars for one host over another. ServerPress acted as a guide, helping customers find the right hosting solutions without bias, allowing them the freedom to choose the best fit. But privately, we knew which hosting providers were naughty and nice. Secretly, WPEngine was on our naughty list, but not for reasons you might suspect.

Our company mantra was to be hosting provider agnostic… ServerPress acted as a guide,… without bias,… But privately, we knew which hosting providers were naughty and nice. Secretly, WPEngine was on our naughty list, but not for reasons you might suspect.

ServerPress had a number of issues with WPEngine long before they acquired Flywheel and launched their restricted, non-FOSS LocalWP software that directly competed with our FOSS-licensed DesktopServer. From the beginning, we faced challenges with WPEngine’s proprietary formatted wp-config.php file, which hindered compatibility. I raised the issue with them at WordCamps, even offering code solutions to improve portability without sacrificing their proprietary features, but they declined—likely to keep migrations away from their platform difficult. Despite our offers to collaborate on a one-click deployment feature that could have brought them on par with other hosting providers and deliver countless new customers for free, WPEngine refused. And I found out why: WPEngine was dropping support for free migration and introduced its own premium paid migration service.

Like WPEngine, ServerPress sponsored WordCamps. But ServerPress also ran “Getting Started” tracks to help beginners get a foothold into the WordPress ecosystem, distributing our open-source creations and blueprints on free jump drives. Doing so bypassed email sign-ups and excessive self-promotion that could threaten WordCamp’s tax-exempt status as a non-profit. Unfortunately, other WordCamp attendees weren’t so compliant and indulged in excessive self-promotion, putting WordCamp in a conundrum. Rather than risk the ire of the IRS and lose the community event, Matt shifted WordCamp to its own corporation and modestly increased attendance fees. Without this change, WordCamps would be no more. Despite LocalWP’s copying of DesktopServer’s blueprint functionality, DesktopServer maintained an advantage with a wide range of support for open-source import file formats (BackupBuddy, BackupWP, Duplicator, and many others). From iThemes to Duplicator, the creators of those file formats were very open and easy to work with. This made it easy to import websites in one click, and DesktopServer had simple FOSS-license installation terms allowing it to be a favorite at WordCamp beginner tracks.

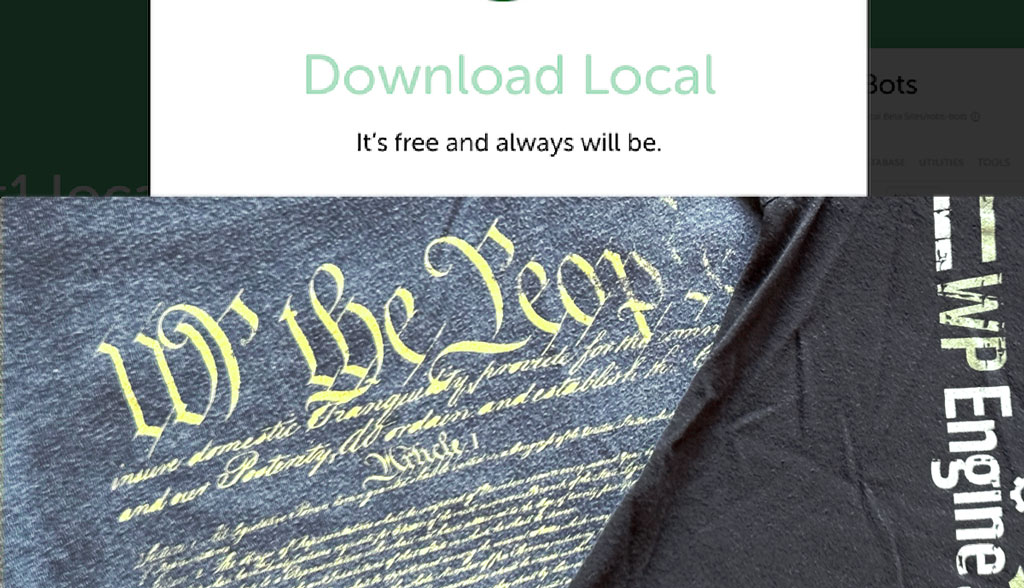

There shouldn’t be a need to inhibit innovation or prohibit others from having the same FOSS rights in order to earn a profit. However, WPEngine went out of its way to muddy the waters by hypocritically confusing the concepts of “free beer” and “freedom of speech”—a distinction that FOSS community members like to emphasize. The tagline for WPEngine’s non-FOSS distribution is “It’s free and always will be,” and this message ran side-by-side with their promotional WPEngine U.S. Constitution t-shirts at WordCamps, conveying a sense of liberties and free rights with their non-FOSS creation.

“…you may not copy, adapt, reverse engineer, decompile, disassemble, or create derivative works of the Software for any reason. WPEngine, Inc. reserves all rights…”. (https://localwp.com/legal/terms-of-service/)

LocalWP license terms

These refusals to participate in open source highlights a common issue in the FOSS ecosystem: when profit takes precedence, community-driven collaboration often suffers, leaving others to bear the weight of maintaining openness.

Freedom Isn’t Free

FOSS promises software freedom, but maintaining that freedom comes with substantial, often hidden costs. Writing the initial code is costly, but maintaining and supporting it can be even more demanding. Copyleft licenses ensure the freedom to modify and distribute software, but they don’t cover maintenance fees. The fact that the vast majority of open-source plug-in developers have been able to bypass these costs for well over a decade should not have been taken for granted. Yet, that has undeniably been the case. At no time has SaaS derived from open source ever been required to be free, even if delivered from or consumed by a behemoth, venture-capital-backed corporation with a sense of entitlement to it. It is extremely important to note that the non-profit WordPress Foundation only covers WordPress core, NOT the plug-in and theme repository servers that are paid for by the commercial company Automattic, Inc. (Matt). Shutting down and/or inhibiting access to those servers for WPEngine was an unprecedented move, and an unfortunate reminder that they are not free.

Some have suggested that the shutdown may be supplemented by another capable provider; for instance, Microsoft-owned GitHub. But even GitHub has bandwidth cap limits and fees (though seldom talked about) that a behemoth enterprise operation like WPEngine would surely be subject to. Updating over 40% of the world’s websites and creating an alternative ecosystem to maintain the code—much less coordinate a community around it for free—is not profitable for Microsoft and will not be without costs. More importantly, without a leader to unite and coordinate that community, it will be difficult to gain traction for success.

Cold Remedy for a Fiery Situation

Neither WPEngine nor Automattic will emerge unscathed from this clash. The lesson here—that prioritizing profit can alienate a community—isn’t new. What’s surprising is that the WordPress community hasn’t faced such an eruption sooner. WPEngine’s model of relying on free services from its primary competitor and former investor is a fascinating case of business strategy and potential self-immolation. Their legal-focused response, lacking a clear plan for their customers, only damages their reputation within the WordPress ecosystem. If they hope to recover, they’ll need to find alternative resources, likely at a far greater cost.

Matt’s response, while not above criticism, should come as no surprise. His unique blend of capitalism, wrapped in a community-driven ethos of “do it for the greater good,” contrasts sharply with the colder corporate world. Some speculate that Matt might abandon GPL, but this ignorant notion seems highly unlikely given the continued success of WordPress and WordPress.com’s premium plugin store, rooted in GPL principles. What it has highlighted is an alternative to plugin updates that are not bound to Automattic’s servers. That functionality exists and perhaps should be researched or audited by agencies concerned with Automattic’s control of WordPress core and plugin updates.

Matt could learn from companies like Amazon or Microsoft: the public might have accepted straightforward terms over targeted community appeals. A clear, firm TOS notice would have sent a direct message to corporate users like WPEngine without naming them. If this were Microsoft or Amazon, the changes would have arrived in a cold, corporate letter, making it clear that “free” doesn’t mean free for enterprise-level providers. Such a cold and direct approach might have prevented this issue from turning into a community-wide brush fire. This, is unfortunately easier said than done. It would require that the next version of WordPress; or the update mechanism itself be re-written to enforce a new TOS clickwrap to receive updates and services. One that doesn’t single out WPEngine with petty checkboxes aimed at WPEngine and their associates but rather any and all revenue generating corporations of a pre-determined size. That’s not Matt’s style but the community might just be better off with clear, concise, and cold facts to drench any fires.