I don’t make it a habit of taking screenshots. That happens on occasion when I fumble with gripping the iPhone’s opposing power and volume buttons; but I do admit to capturing my mother smiling. Sadly, those unique opportunities have come to an end. Now I cannot feel bitter or alone. That would break my mother’s heart. I know that I’m not alone in this exceptionally tragic past year. 2020 brought the death of my father in April, my sister in July, and my mother at the turn of the new year. Her diagnosis as COVID positive on Christmas Eve came after a long list of updates and bulletins for the area; for California; for America; for the world. We knew she would not fair well with her preexisting condition; years of Parkinson’s disease had taken its toll. Mom was a fighter and survived some of the harshest circumstances of war; having lost her own sisters and father in conflict while trying to flee from Northern to Southern Vietnam. She knew first hand the harsh circumstances of an indifferent authoritarian regime. Although already independent, she became an orphan in her teens having lost her own mother (my grandmother) to tuberculosis; a devastating disease generally affecting the lungs. Tuberculosis in the United States would see a dramatic reduction in the 1970s thanks to organized and competent leadership that promoted education and awareness; while technology delivered a viable vaccine. The conforming modern America of unquestioned contact tracing, and mostly free TB testing exists to this day. America was the place to be and that was where she would safely raise her family.

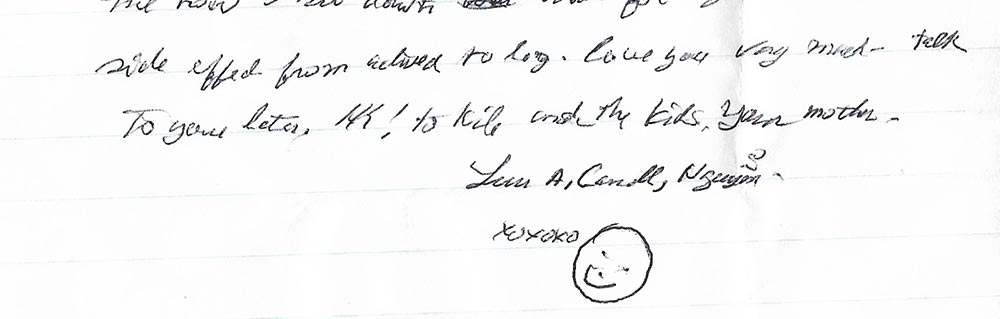

When the call came in that mom had been admitted to John Muir Hospital with a high fever, I felt the immediate need to rush to her side. I told my coworkers over Zoom that I would have to go despite knowing better; I get daily stories being married to a busy city hospital ICU nurse. Yet the facts seemed distant and unrelated; this was my mother. She was the kind of mother that held a constant, genuine, undying concern, and love for her only son. Mom’s ability to do Gansai (顔彩) art painting, much less hold a pen, had degraded heavily over the years but she still wrote letters by hand and signed with love, x’s & o’s, and a handwritten happy face; the emojis of her era. I had to be by her side.

My mother’s religious beliefs paralleled her home country’s practice of Catholicism and Buddhism and my urgency to be with her came from my own spiritual practices. It was the Vietnamese peace activist and Nobel nominated Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh that brought peace to my earlier life and death anxieties. I read Hạnh’s book, No Death, No Fear after losing a friend in my thirties and experiencing a round a depression. It became a great source of comfort as he explained the events of death, its many permutations, and even the parting of his own mother. Within one of his passages was a message about comforting the dying and it conveyed being there in person:

“When you sit by the bedside of a dying person and you are calm and totally present in body, mind, and soul, you will be successful in helping that person pass away in freedom.”

Hạnh, Thích Nhất. No Death, No Fear

COVID and distance would make it risky and impractical to be there in person; but technology could help make it less painful in an instant. It goes without saying that the warm touch of a human hand would be preferred over a cold glass display. However, as often is the case with the dying, time is of the essence. Through tech I was able to be with her as further medical technology eased her physical pains and carried her off into comfort care; a deeply pain free state she had not known for years. I can only be thankful and full of gratitude to see her one last time. She would not have to wait for my arrival. She would not have to linger in pain. The living younger of my two sisters would join me as two nurses approached her bedside with digital tablets in hand. My logical concerns about COVID exposure were confirmed as the nurses were dressed in full PAPR (powered air-purifying respirator); a hazmat-like suite. I was mixed with emotions of dread that mom would have to witness such dire attire; but relieved that it afforded an unmasked and full view of angelic nurse faces behind clear plastic; allowing her to see expressions of authentic concern for her comfort. Each nurse used the tablets, a magic mirror given the situation, to project our voices and images in her direction; mere inches from her face. Mom initially kept her eyes closed but she could hear us and our repeating message of love and peace. The repeating love and peace message as suggested by the Vietnamese Buddhist monk I studied earlier.

In his book, Thích Nhất Hạnh alleviates the turmoil surrounding living and dying by explaining our notions of birth and death, of coming and going, as ever changing manifestations. His talent for clarity and simplicity parallels the often touted western philosophy of: “your loved one lives on within you”. His depth and eloquence goes farther than I ever could with suggestions for exercising mindfulness and how it can comfort the living and the dying. While Hạnh’s spiritual messages mostly draw in the beauty of the natural outdoors; he does not oppose the very nature of technology; a stark contrast to the brand of Taoism and anti-technology sentiments that have hypocritically invaded American politics. In fact, the Buddhist monk uses references to modern technological innovations as analogies to explain life’s many manifestations and how to best comfort the dying. He states that everything endures, but in different forms. The scientific law of conservation also comes to mind.

…we may think that television programs and radio programs do not exist in that room. But all of us know that the space in the room is full of signals. The signals of these programs are filling the air everywhere. We need only one more condition, a radio or television set, and many forms, colors and sounds will appear. It would be wrong to say that the signals do not exist because we did not have the radio or television to receive and manifest them…

Hạnh, Thích Nhất. No Death, No Fear

Our consciousness is like a television with many channels. When we push the button on the remote control, the channel we choose appears. When we sit by the bedside of a dying person, we have to know which channel to call up. Those who are closest to the dying person are in the best position to do this.

Mom was too weak to be able to speak. My sister and I watched and spoke to her as she laid in the hospital bed. Like magic, our present moment of love and concern transmitted through hundreds of miles of network fibers and through the air to her bedside. I am grateful for the nurses to be there. I have gratitude for the technologists that made our digital presence possible. I am thankful to be able to see the photons of light that bounced off her face and into the sensors of the tablet to relay her micro-expressions; it allowed us to understand her present state of being; it allowed us to judge her level of pain and comfort; it allowed us to know it was time to say goodbye. We repeated our love for her over and over again; and I spoke in her native tongue for the last time, “con thương mẹ”; I love you mom. She lifted her left eye to see us one last time and summoned the strength to bend her arm slowly, untangle it from the oxygen line, and bring her hand to her mouth. The nurses started to speak, “She is blowing you kisses”. We could see the gesture through the pixels on our screen. We could feel the love of our mother. In that moment I could feel calm and totally present in body, mind, and soul and felt fortunate in helping mom pass away in freedom; for that I will always be grateful.

Sending love and comfort to you and your loved ones Steve.

Dear Stephen,

Toby just texted me that your mom died. I am so sorry! Your mom had a very challenging life full of ups and downs, but she persevered and always loved her children. Losing a mom is so hard, no matter what age we are — it leaves such a big hole, and I know you will miss her.

This year has been so hard for you and Marina, made doubly hard by the virus and not being able to travel. It has fallen to you to settle three estates in the most trying of circumstances, and yet you, too, have persevered.

I hope travel will be allowed this summer so that you can come to Colorado; i look forward to seeing you then, love, Aunt Cheri

RIP your Mom

What a year it has been for you losing your love ones.

This blog is wonderful and thankful for technology.

Thank you for sharing

Wishing you the best vibes and love.

– Candy

Stephen, we are so sorry for the losses you and Marina have experienced recently. I am so glad you got to say goodbye to your mother, it’s so painful when you can’t.Dan and I are always here for you . With all our love Dan and Debbie.

Stephen, Your words are so beautiful. I am so sorry for your loss. I am so glad that you could be connected with you mom in these moments.